Large Brains in Autism: The Challenge of Pervasive Abnormality

Neuroscientist. 2005 Oct;11(5):417-40.

Large Brains in Autism: The Challenge of Pervasive Abnormality

Herbert MR., Harvard University

Pediatric Neurology, Center for Morphometric Analysis, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charleston, MA

Abstract

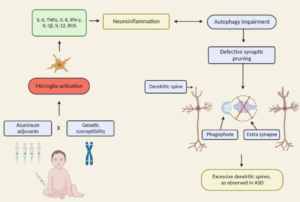

The most replicated finding in autism neuroanatomy-a tendency to unusually large brains-has seemed paradoxical in relation to the specificity of the abnormalities in three behavioral domains that define autism. We now know a range of things about this phenomenon, including that brains in autism have a growth spurt shortly after birth and then slow in growth a few short years afterward, that only younger but not older brains are larger in autism than in controls, that white matter contributes disproportionately to this volume increase and in a nonuniform pattern suggesting postnatal pathology, that functional connectivity among regions of autistic brains is diminished, and that neuroinflammation (including microgliosis and astrogliosis) appears to be present in autistic brain tissue from childhood through adulthood. Alongside these pervasive brain tissue and functional abnormalities, there have arisen theories of pervasive or widespread neural information processing or signal coordination abnormalities (such as weak central coherence, impaired complex processing, and underconnectivity), which are argued to underlie the specific observable behavioral features of autism. This convergence of findings and models suggests that a systems- and chronic disease-based reformulation of function and pathophysiology in autism needs to be considered, and it opens the possibility for new treatment targets..

Excerpt: “Oxidative stress, brain inflammation, and microgliosis have been much documented in association with toxic exposures including various heavy metals…the awareness that the brain as well as medical conditions of children with autism may be conditioned by chronic biomedical abnormalities such as inflammation opens the possibility that meaningful biomedical interventions may be possible well past the window of maximal neuroplasticity in early childhood because the basis for assuming that all deficits can be attributed to fixed early developmental alterations in neural architecture has now been undermined.”