Another Step Toward Defining an Immune-Mediated Subtype of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Invited Commentary | Pediatrics, June 8, 2018

Another Step Toward Defining an Immune-Mediated Subtype of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Christopher J. McDougle, MD1,2

1Lurie Center for Autism, Massachusetts General Hospital, Lexington

2Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180280. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0280

Original Investigation

Association of Allergies With Autism Spectrum Disorder

Guifeng Xu, MD; Linda G. Snetselaar, PhD; Jin Jing, MD, PhD; Buyun Liu, MD, PhD; Lane Strathearn, MBBS, FRACP, PhD; Wei Bao, MD, PhD

In their article “Association of Food Allergy and Other Allergic Conditions With Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Xu and colleagues present new data that add to the growing body of literature supporting an immune-mediated subtype of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The investigators analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey, a continuous, ongoing, nationally representative annual health survey conducted in the United States since 1957. The National Health Interview Survey is the primary source of information on health conditions of the US population. Data from 1997 to 2016, collected via an in-person household interview, were used in this study. All children aged 3 to 17 years with available information about allergic conditions and ASD were included. Respondents were asked about the occurrence of a food or digestive allergy, any kind of respiratory allergy, or eczema or any kind of skin allergy during the past 12 months. Respondents were also asked whether the child received a diagnosis of ASD from a physician or other health professional. Among the 199 520 children in the analysis, 8734 had food allergy, 24 555 had respiratory allergy, and 19 399 had skin allergy. Health professional–diagnosed ASD was reported in 1868 children. Children with ASD were significantly more likely than those without ASD to have food allergy (11.25% vs 4.25%), respiratory allergy (18.73% vs 12.08%), and skin allergy (16.81% vs 9.84%). The likelihood of the child having ASD more than doubled among children with food allergy compared with those without food allergy; children with respiratory and skin allergy were also significantly more likely to have ASD, but at a lesser magnitude. While no sex difference was found for food allergy, boys with ASD were significantly more likely than girls with ASD to have respiratory and skin allergy.

Previous studies have identified a positive association of respiratory allergy and skin allergy with ASD, as detailed in the current article. To my knowledge, the results of Xu et al are the first to document the association of food allergy with ASD with confidence, in part based on the large sample size they accessed. The authors wonder whether this association may be related to gut-brain-behavior axis abnormalities that have been hypothesized to exist in a subset of individuals with ASD. Such an association has been reported in both patients with ASD and animal models of ASD, particularly those using the maternal immune activation model of ASD.2 From a clinical perspective, patients with ASD who are minimally verbal to nonverbal may be unable to describe the pain and discomfort they experience secondary to food allergy and subsequent inflammation in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Instead, their physical distress may manifest as irritability, aggression, and/or self-injury. It is important to underscore the need for health care professionals to conduct a thorough history and physical examination to rule out identifiable medical causes of aberrant behavior, including food allergy and secondary GI inflammation, before proceeding with treatments designed to reduce behavior problems. In addition to GI pathology, other common comorbid medical disorders that occur with ASD include seizures and sleep disturbance. Interestingly, each of these comorbidities has also been associated with inflammatory processes. It may be that GI dysfunction, seizures, and sleep disorder, in addition to food, respiratory, and skin allergies, are medical comorbidities that characterize the immune-mediated subtype of ASD.

Another interesting and potentially important finding in the current article is the lack of significant association of respiratory allergy and skin allergy with ASD in girls. These findings are in line with recent reports of a striking difference in vulnerability to early-life immune insult between male and female mice in animal models of ASD.

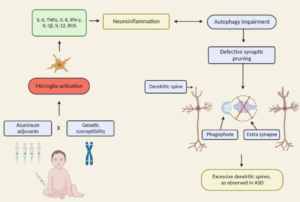

In the Discussion section of their article, Xu and colleagues review other aspects of immune dysfunction reported in ASD, including abnormalities in peripheral immunoglobulins, imbalance of T-cell subsets, and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines in postmortem brains of patients with ASD. Considering the significant association between food, respiratory, and skin allergy in children with ASD reported by Xu and colleagues, in conjunction with numerous studies documenting aspects of immune dysfunction in patients with ASD and specific animal models of ASD, evidence continues to mount that an immune-mediated subtype of ASD should continue to be pursued and defined.